The root cause of Ethiopia's foreign currency woes

The foreign currency shortage in Ethiopia is perhaps the most consequential yet most misunderstood economic reality in the country today. Maximizing foreign currency reserves is all that anyone talks about in terms of economic policy, but the centrality of foreign currency in all our economic discussions owes more to our misunderstanding of the forces behind the current foreign exchange shortage than any special worth foreign currency has to our economic system.

The dominant conventional view driving much of Ethiopia’s economic policies can be summarized as follows: We have a shortage of foreign currency because we import too much and export too little. If this is your framing of the problem the solution is obvious. We need to export more and import less. The singular monopoly this narrative holds over Ethiopians' collective understanding of the forex problem can not be understated.

This formulation holds such a stranglehold in the public imagination that import substitution has become Ethiopia’s predominant policy goal as a solution. By domestically producing more and more of the goods we used to import, someday we will be “self-sufficient”. This is the overriding policy goal of most government ministries in Ethiopia. (See here (opens in a new tab), here (opens in a new tab) and here (opens in a new tab)). It sounds plausible. And yet despite the dominance of this economic narrative in shaping Ethiopia’s domestic and foreign policy agenda, it is simply wrong. It’s a fallacious narrative that is used to prop up Ethiopia’s current ruinous foreign exchange regime and as such stands as the greatest obstacle impeding Ethiopians from enjoying a prosperous economic future.

Foreign currency and prices

The foreign currency shortage in Ethiopia is not an import problem, but a pricing problem. The official foreign currency exchange rate maintained by the Ethiopian government is a form of price control that has all the trappings that come along with it.

What happens when governments impose an artificial price on something at well below its market price? You end up with shortages and black markets. Remind you of anything in Ethiopia?

To understand this better let’s substitute foreign currency with cars and start with a thought experiment. What would happen if the National Bank of Ethiopia changed the price of cars to half the market price. Let’s say the government decrees a maximum price ceiling of one hundred thousand birr on all vehicles in the car market today. What would happen when selling cars above this “official” price is suddenly outlawed? The result would be a quick shortage of cars. The demand for automobiles priced at a hundred thousand birr is infinitely higher than the supply and as such you would get an almost instantaneous shortage as people flood into auto shops to buy as many cars as they could. But let’s go even further and imagine a price ceiling of just ten thousand birr. The shortage would manifest even quicker, as there are thousands more people who can muster up ten thousand birr compared to one hundred thousand.

Even though this is an extreme example it illustrates the consequences of imposing an artificial price ceiling which Ethiopia’s so-called “official” foreign exchange price is but one example of.

To fully grasp how shortages manifest under a system of price ceilings, one has to go a few steps back and understand how prices operate in a market economy and their crucial role in resource allocation.

But first let’s start with what prices are not. Prices are not arbitrary numbers plucked out of the air by businessmen with complete power over them. This happens to be the conventional view in Ethiopia where prices are subject to the whims of self-interested businessmen. If that’s your understanding of prices it is a no-brainer that the government should be in control of them. Why allow prices to be subject to the vagaries of self-interested businessmen when the government can set prices with the public interest in mind? Indeed, this explains the expansion of price control as a policy in many areas of Ethiopian life today, from city transportation (opens in a new tab), to the price of cement (opens in a new tab), gasoline (opens in a new tab) and even bread (opens in a new tab).

But if business greed is the driving force behind prices, why don’t we pay more for the price of goods today? The price of teff has recently soared to a new high of 78 Birr (opens in a new tab) per kilo. But if greed was the driving factor, why would it stop there? Why didn’t go to a 100, or even more? Why don’t we pay 10% more for all the goods available in the shops today? Or 20? If greed was the controlling factor there would be no end to rising prices as greed is limitless.

Moreover we would never see falling prices if greed was the driving force. But even in Ethiopia, where it’s long been fashionable to believe that prices rise but never fall, prices do drop. On the days following a holiday, there is a noticeable drop in the price of chicken and sheep. Is this because sheep peddlers become collectively less greedy overnight? If that were so, the way to get rich as a sheep peddler would be to go against the grain and keep charging high prices in the days after. This is where greed as an explanation falls flat. Greed is an ever constant. What changes are circumstances of supply and demand which are the true driving force behind changing prices.

In a market economy prices reflect changing realities in supply and demand. Ultimately it is this information, expressed through prices, that controls resource shifts between various industries. The true function of prices is to allocate scarce resources with alternative uses to their most valued ends. Put simply, prices determine how much of a given resource is used to produce one good vs another. For example, what percentage of the wood available in Ethiopia, is used to manufacture paper as opposed to its other uses, is determined through price bidding. When there’s an increased demand for more paper, paper manufacturers will bid up the price of wood to acquire it in higher quantities. This then has knock on effects on how wood is allocated between other industries where wood is a raw material. These industries now also have to pay a higher price for wood which inturn increases the price of their products. And if customers of wood tables are less willing to tolerate rising prices compared to other wood industries, say wood flooring, then a larger portion of the new wood that goes into making paper will come at the expense of wood furniture as compared to wooden flooring. Furniture makers will be forced to cut back on producing wood products to avoid losses. To produce the same amount of furniture as before, they either have to wait for the wood supply to grow causing prices to fall to previous levels, or come up with more efficient ways to utilize the smaller quantity of wood available to them. This is how prices guarantee that overtime resources flow to their most valued uses. All of this happens automatically without a government bureaucracy directing the production and allocation of wood.

Similarly in countries where the price of foreign currency (a scarce resource like any other) is determined through such market forces, how much foreign currency is allocated to importing one good vs another is determined through supply and demand. When there is a spike in demand for imported smartphones as compared to microwaves, then smartphone importers will have a capacity to bid a higher price for the foreign currency they need to import their goods. The increase in smartphone imports will come at the expense of microwaves or other goods less in demand. Through this bidding process importers with the highest demand for their products will be able to acquire more foreign currency than their competitors.

And just as changing demand shapes resource allocation, so do changes in supply. When availability of foreign currency shrinks, perhaps through falling exports in an important industry, the price increase will force importers to economize on the available foreign currency. Less is imported overall. More of what’s less in demand stops being imported and less of what’s more in demand is impacted. Conversely when the supply of foreign currency increases (say because remittances hit new highs), lower prices will ensure not just that more of the stuff that’s already imported comes in, but that new markets will open up for new imported goods.

To understand this in better detail, let’s imagine for a moment that a ship carrying a large shipment of goods to Ethiopia sinks somewhere in the pacific Ocean. Let’s assume this shipment was carrying large quantities of much needed consumption items including food, clothing, electronics, etc. The shortage that would follow is likely to drive up the price of these goods. Supposing Ethiopia had a free market for foreign currency, the rise in demand for these imported goods would cause a similar demand spike in the foreign currency market, causing the price of dollars or euros to go up.

Terrible as this shock may be, the price increase is actually a necessary step towards addressing the problem. A price increase is a signal that more forex supply is needed. Members of the Ethiopian diaspora enticed by higher prices on foreign currency will be incentivised to exchange more of their dollars to birr under the new circumstance. There will be an incentive towards expedited exports in the export industry as exporters are enticed to get deals over the line quicker and acquire foreign currency while the price is at a premium, to say nothing of the long term planning and investments that spin up to capitalize on attractive export returns. The price hike on imported goods also acts as a signal for domestic consumers to conserve the goods already available to mitigate increased scarcity.

Again all of this happens in real-time with no one person or committee in charge of directing how much of any given resource goes here or there. In the end consumer demand choices, expressed through fluctuating prices, dictate the underlying reality of resource allocation.

Price control and its impacts

But what happens when a government departs from such a system and sets the effective price of foreign currency well below the market price as the Ethiopian government has been doing for decades now? You get the kind of chronic foreign currency shortage Ethiopia has been experiencing.

Price controls disrupt the critical role of prices in transmitting information of changing realities in supply and demand. For the foreign currency market the effects of price control manifest themselves in the import industry because the main function of foreign currency is to buy goods from abroad. Imposing artificial price ceilings on foreign currency is effectively the same as sending out the false information that there is more supply than exists and less demand than there actually is. At this artificially low price a higher number of importers vie to acquire foreign currency at higher quantities than they would had increasing prices been allowed to transmit the real supply information. The artificial price creates a level of demand that can not be met by the existing supply resulting in chronic shortages. The shortage of foreign currency reserves in Ethiopia is simply a function of artificially low prices set by the government.

Another way of looking at it, is that the artificial price amounts to a windfall subsidy for importers lucky enough to obtain foreign currency at an artificially depreciated price especially when the artificial price stands at almost half the real price as is the case with dollars in Ethiopia today. Imagine being able to acquire anything at half the price, much less foreign currency. A shortage is guaranteed.

But if that wasn’t bad enough, price control has a similarly deleterious impact on supply as well. Less returns from artificially low prices effectively sends out the information to forex suppliers of a more saturated market where less foreign currency is in demand. This has repercussions in the remittance space and export market where there’s less participation as a result. How much of anything would you buy if you were forced to pay double the market price?

But the impact continues. Removing the role of prices in mirroring supply and demand also means that prices no longer serve their natural function of rationing resources between competing ends. When there’s not enough foreign currency to go around due to artificially lower prices, some other means of rationing needs to be devised. The government’s answer to this has been to disallow (opens in a new tab) wholesale import industries of which it disapproves. But it is important to understand that such rationing is not a natural phenomenon governments have to do. It is only necessary because the role of prices in regulating allocation flows has been destroyed.

The end result of all this has been a chronic shortage of foreign currency in Ethiopia spanning decades.

Forex Nationalization

Price controls in general have been devastating for particular sectors of the Ethiopian economy. A prime example is Addis Ababa’s transportation sector where price controls have led to the predictable combination of chronic shortages, quality deterioration and black markets. But as disastrous as price control is in such isolated sectors, its application to foreign currency has been especially ruinous because its effect isn’t similarly confined to one sector of the economy but plagues the entire import industry.

Had foreign currency been a mere consumption item like onions or potatoes, the bad effects of the shortage would be sequestered to one item for which other substitutes exist. But foreign currency is special in that it’s the only item with which all imported goods are acquired and for which no other substitute exists. Mess up foreign currency and you mess up the entire import industry which is exactly what price control does.

And the policy in place on foreign exchange is not one of mere price control, but full-blown nationalization. Since it’s hard to enforce price control policies on foreign currency under conditions of widespread ownership, the government resorts to outright confiscation of currency from the population. Why chase down illegal transactions when you can outright ban currency ownership and possession. As such, it is illegal to possess foreign currency in Ethiopia for more than a few weeks. Violating this law comes with a potential 15 year prison sentence (opens in a new tab).

Such draconian measures have given the government monopoly power over foreign currency and turned it into full central planning authority over the entire import industry. It’s hard to call Ethiopia a market economy today when the entire import industry is in the grip of government control.

What makes central planning of forex and imports so catastrophic to the economy?

To answer that we have to ask another question. How much of our foreign currency reserves should go to importing laptops or books, how much of it should go for expense allowances for Ethiopians studying or traveling abroad? There are millions of things that can be imported and an infinite amount of ways to allocate foreign currency between them? How do we even know if we should import something, much less how much of it to import? This question is ultimately unknowable by any person or committee because human choices are infinite and priorities change day to day. The only way to approach an optimal answer without anyone having to guess is by allowing the forces of supply and demand to dictate the allocation of foreign currency through honest pricing. In a market system people only have to keep track of the price of foreign currency with respect to the few goods they’re importing. No one person or group of people have to know, a priori, where all the forex needs to go. If there is a surge in demand for diabetes drugs, importers can bid more and increase the amount of foreign currency available to them. This takes foreign currency away from other uses with comparatively less demand.

But the erasure of supply and demand information under the price control system means foreign currency has to be allocated blindly. This has led to the disappearance of life-saving medicine, causing stories like the one in this article (opens in a new tab), where Tollera Dagne, a father of 7 went for weeks unable to find medicine to slow the spread of a cancerous tumor he was diagnosed with. There are also examples (opens in a new tab) of painful shortages of insulin and blood pressure medicines among other countless drugs.

None of this should be surprising. Central planning which works without the information and incentives of supply and demand is blind planning. Government bureaucrats can’t allocate foreign currency in the realm of pharmaceutical drugs let alone all the other uses foreign currency could be put towards. There is no central body that can know which drugs to import out of the countless drugs in existence around the world, much less know how much of each needs to be imported.

But the problem is twofold. Not only does central planning cause shortages if not outright disappearance of overlooked goods, but it also causes a surplus of goods that get imported too much. Some goods that are deemed more necessary than others by central decision makers get more foreign currency access than they would under market conditions which creates the possibility of some imported items sitting on the shelf for a long time while painful shortages plague other overlooked goods.

Central planning also opens up the prospect of foreign currency allocation through political and corrupt means. In Ethiopia, millions of dollars of scarce foreign currency is currently financing the construction of a new prime ministerial palace (opens in a new tab) which consists of three artificial lakes, private roadways on 503 hectares of land, and a hotel. Different estimates put the final cost of the project somewhere between 490 million to 8 billion dollars. Under a central planning regime which ultimately answers to the Prime minister, such opulent and exorbitant outlays take priority in terms of foreign currency availability over the needs of the average Ethiopian whose demand has no representation in the foreign currency market. Political decision making completely supersedes market dynamics.

And the implications of supply and demand go much further than the allocation of forex to existing sectors. Under a market system, new businesses that import goods and capital and carry out their businesses more efficiently than existing businesses will pull away more of the supply of foreign currency towards themselves and away from businesses less efficient in managing their resources.

Under Ethiopia’s current exchange regime however, the door is closed on new businesses and ventures who would otherwise prove their worth. Only ventures that are effectively pet projects of people in power get the green light. Stopping market forces from weeding out inefficient ventures has meant that projects that waste foreign currency resources keep that privilege as long as they are sufficiently connected politically. They are insulated from competitive market forces that punishes ventures that waste foreign currency and rewards those that use it efficiently.

How many businesses that would have grown into powerhouses of industry don’t exist today as a result of this policy? How many businesses have approached key growth junctures and had to stagnate and ossify because they have no access to forex? How drastically different would the terrain of Ethiopian industry look were it not for this policy? Ultimately this is unknowable. And even though some would dismiss this line of thinking as a counterfactual, the whole point of economics is to analyze what is seen and what is unseen. The damage wrought by many government policies are unseen. There is no special interest for businesses that would have existed, for employees that would have had jobs were it not for this policy. What can be said for sure by analyzing incentives and constraints, is that government veto power over foreign currency in Ethiopia has stunted market democracy and is perhaps the biggest impediment preventing the country from developing a strong, competitive and dynamic economy.

Hoarding

Another consequence of price control is an increasing number of customers wanting to hold on to a larger than usual inventory due to fears they might not be able to get a hold of them in the future. This in itself creates further pressure on demand exacerbating the shortage. The market for insulin medication has fallen victim to this phenomenon (opens in a new tab) where the uncertainty created by the environment of pharmaceutical drug shortages has induced more people to stockpile insulin at home despite the insistence of pharmacists that there is enough supply to go around. This is how one pharmacist at Kenema pharmacy describes it:

Citizens have reached a point where they do not trust the government. They buy as much as they can, in increased quantities, even though we tell them there is enough stock. And when they accumulate a shortage occurs.

This increased demand in turn caused the price of insulin to go up leading to a predictable government crackdown on pharmaceutical importers for effecting a 100% price spike.

But the ultimate cause of the hoarding can be traced back to the forex shortage that follows from the absence of supply and demand information in the foreign currency market. Where rationing of foreign currency is done through health bureaucrats who simply cannot know all the drugs available in the world, let alone how much of each is needed in Ethiopia, the end result is a shortage of many drugs. And as the shortage gets worse as a consequence of the currency valuation gap, an increasing number of drugs are affected in turn fueling fears of an impending shortage even for those drugs for which there is enough short-term supply, causing price hikes across the board.

Another consequence of this rationing regime is a surplus of other medicines, a black market for medicines afflicted by the shortage, and quality deterioration in the types of drugs available.

Under a system of centralized forex allocation the types of people that commonly lose out are people with rare diseases requiring uncommon medication. No matter how much of their income and wealth they are willing to allocate for treatment, even if they’d be willing to sell their property wholesale they won’t be able to acquire it through official channels because of the nature of the forex regime. The article (opens in a new tab) goes on:

Medicines which are not produced in large quantities are being sold on the black market because there is little demand for them, so they aren’t imported because of the dollar shortage. ‘Antitoxin is a drug that is prescribed to treat rusty metal wounds. Even though it is a drug that should be kept in the fridge, it is being put on the market after being smuggled recklessly through the desert.’

Black markets

Another consequence of price ceilings is the formation of black markets. The foreign currency black market in Ethiopia is practically an open secret. And increasingly it is where a significant percentage of all forex exchange occurs. It’s hard to say how much, as black market actors have a strong incentive to remain anonymous, but growing denunciations (opens in a new tab) of the black market system by government officials is an indication that it’s a growing trend. And it will only continue to grow, to the extent that the gap between the black market price (which is closer to the true forex market price) and the artificial government price grows wider.

Many economic commentators in Ethiopia have a backwards view of the black market price. There is a widespread assumption that the black market price is always destined to rise by an amount far in excess of the “official” price no matter the “official” price level. The thinking goes that if the “official” price of the birr is devalued by say 50 percentage points to 82 Birr, it would cause the black market price to jump by at least the same amount if not more. According to this view the “official” price acts as a controlling force on the black market price. This is used as an argument not to raise the “official” price for fear of an explosion in the black market price.

This view is best expressed by Ashenafi Endale (opens in a new tab):

The … issue is that it is difficult to reunify the official and black markets, since the black market is always a moving target.

For instance, if the NBE devalues the birr by 75 percent, the official exchange rate increases from 53 birr now to almost 93 birr per US dollar. However, there is no guarantee that the parallel market rate will not double from around 100 birr at the moment.”

There are a number of problems with this argument. Firstly, if the “official” price is a controlling force on the black market price such that increasing the artificial price results in a rise in the “black market” price, then it stands to reason that reducing the “official” price would correspondingly reduce the black market price. Yet strangely you never hear devaluation doomsayers make the case for actively strengthening the birr as a means of tamping down the “black market” price. It’s a one-way equation for some reason.

Secondly this narrative confuses correlation and causation. The explanation for the drastic spike in black market prices is that government money printing to finance ballooning government debt has led to the Birr’s drastic collapse. And given that it would be foolish to print money while leaving the “official” price intact, as doing so would have exacerbated the severity of the shortage even more, the government probably devalued the “official” price in tandem with its pursuit of monetary expansion (money printing). So it’s no surprise that the black market value and the “official” value would fall around the same time, but the cause for both is monetary expansion. To look at both devaluations and designate the “official” devaluation as the cause of the Birr’s fall in black-market value is akin to telling a flu patient that it’s the cough that’s causing the sneeze.

There is no magic principle by which black market prices continue to exist at perpetually higher prices than market prices. Prices follow vicissitudes of supply and demand. The issue here is that prices have been prevented from expressing this underlying reality. If true prices were allowed, there would be no shortage and hence anyone capable of paying the market price will be able to acquire as much foreign currency as they can pay for. A black market wouldn’t exist in that scenario because it would be a fool’s market. Individual foreign currency sellers can price their dollars at twice the market rate, just as street peddlers can price say bottled water at one thousand birr a pop. The question is why would anyone pay that much?

The devaluation mirage

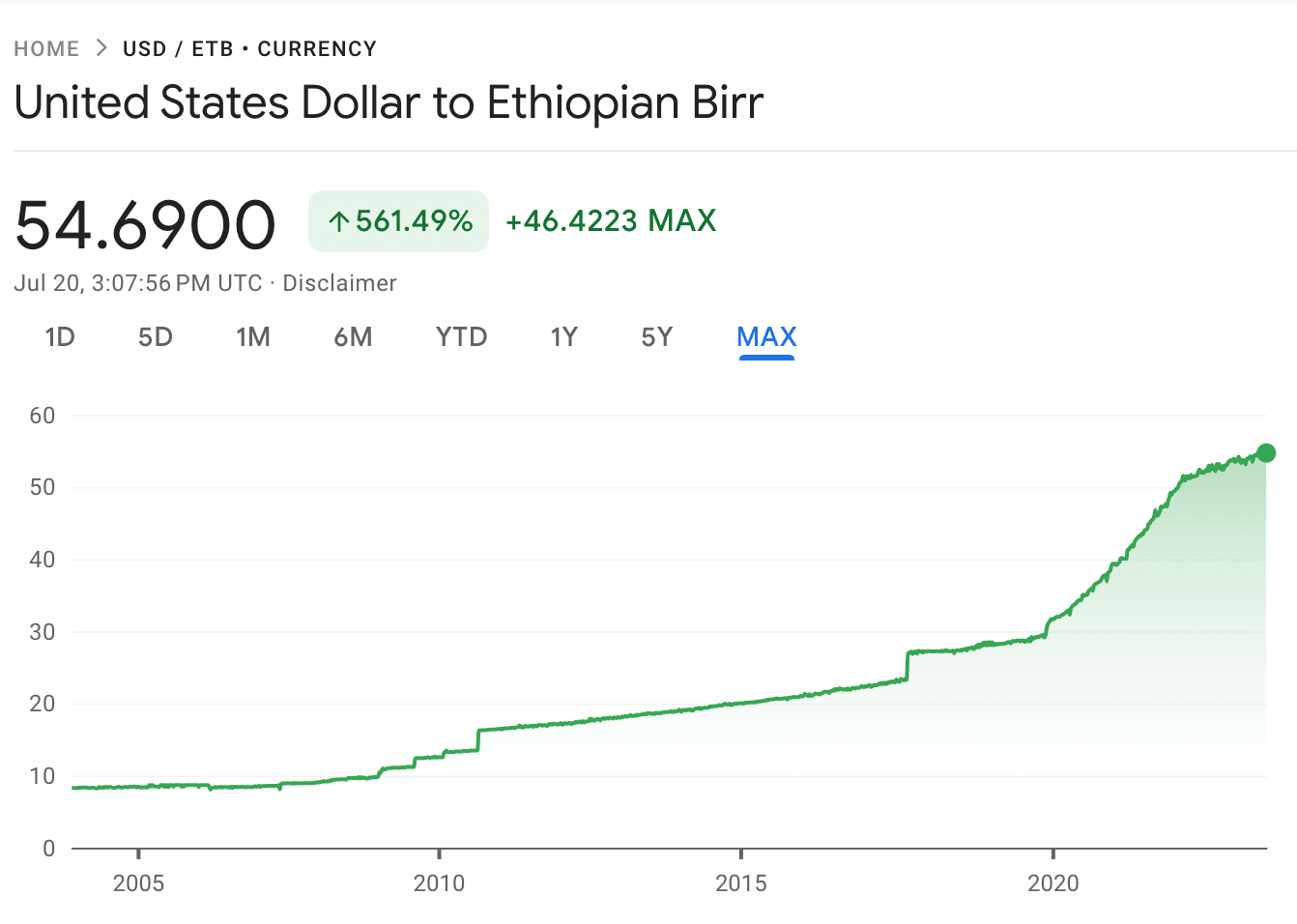

Under a price ceiling regime the intensity of the shortage mirrors the gap between the artificial price ceiling and the true market price. In other words, the bigger the gap between the artificial price ceiling and the actual market price the more chronic the shortage. In recent years this gap in Ethiopia’s foreign currency market has been growing steadily larger, exacerbating the shortage and dwindling the national foreign currency reserve more than usual.

Yet, initial appearances would say otherwise. The government has been lowering the “official” price of Birr in relation to the dollar at an accelerated pace over the past 3 years.

This suggests that the Birr has been devalued and brought closer to its true price. Yet if that’s the case, why has the shortage gotten worse when it should have been getting better.

To understand why, one has to start thinking in terms of real prices as opposed to the fictional prices maintained by the government. The answer lies in the fact that the real price of the birr in terms of other foreign currencies has been falling at a faster rate than the rate at which the artificial price has been adjusted down, meaning that in real terms the Birr was being strengthened not devalued.

When a currency is debased through government money printing its value drops in relation to other currencies. Take a currency that is price controlled at 0.1 dollars per unit when its real value (absent government price controls) would have stood at 0.2 dollars per unit. Suppose that the government inflates the currency so much that its real value depreciates to 0.4 dollars per unit(a 100% devaluation). But the government only adjusts the artificial price down by 50%, devaluing the “official” rate from 0.1 to 0.15 dollars per unit. The government can claim to have devalued the currency by 50%, but in real terms the artificial price has been strengthened against its real value, not devalued. The dollar price ceiling has been lowered, not raised.

The Ethiopian government has been on an accelerating course of monetary expansion (money printing) for a number of years now which has devalued the birr a great deal. In fact, much of the rise in the recent cost of living can be attributed to this phenomenon. And for the price ceiling on foreign currency to have stayed at previous levels(never mind being brought closer to its real value) the Birr had to be devalued more than it was. Yet the Birr was only “devalued” conservatively even as it was being expanded recklessly. This meant that the Birr was effectively being strengthened even though initial appearances suggest otherwise.

Devaluation and Inflation

There is an enormous pressure campaign in Ethiopia against the prospect of liberalizing the foreign currency market on the pretext that doing so would spark an economic shock of soaring prices of imported goods. The economist Alemayheu Geda, a firm proponent of this view, says (opens in a new tab):

When the exchange rate increases, the price of imported goods increases with it, causing more inflation leading into a vicious circle we call inflation devaluation spiral

While journalist Samson Berhane says (opens in a new tab):

Floating the birr without enough foreign exchange would be a disaster as it would cause the prices of imported goods to go up, given the country's reliance on imported goods. Other countries' experiences suggest that hyperinflation is possible under these conditions.

This view is not without theoretical grounding. Since foreign currency is what’s used to buy all imports, the thinking goes that increasing its price will increase the price of imports. But what this fails to take into account is that most imports today are financed via currency obtained from the black market. For the bulk of the import market, a spike in the artificial price is a non-event. The brunt of the damage will mostly be concentrated on import-dependent public industries that currently enjoy favored status above private industries in terms of currency access. And even though the government will talk up their importance it is hard to estimate the necessity of public industries to the standard of life of the average Ethiopian. This is because public corporations don’t live or die by market pressures, but are maintained through subsidies. And there is no shortage of inefficient money-sink public corporations in Ethiopia from the famed sugar corporations with over 7 billion birr in reported losses (opens in a new tab), to Sheger Dabo factory which recorded a whopping 70 million birr loss (opens in a new tab) in a period of just 5 months, not to mention the millions of dollars that flow into government building construction and renovation projects. How much of the 2.2 billion birr (opens in a new tab) spent on renovating Addis Ababa’s municipality office consisted of forex payments? How much for the 2.1 billion birr (opens in a new tab) spent on INSA’s new headquarters building?

But the problem is not just the forex that goes into propping up inefficient public industries. Even for the industries where foreign currency allocation is universally agreed on as an absolute must (i.e. Pharmaceutical drugs), the absence of supply and demand information creates inefficiencies. More of what’s needed gets imported for some types of life-saving medications while not enough for others.

Furthermore, not allowing price hikes is ultimately the main impediment against falling currency prices as it prevents the information that more supply is needed from being priced in.

But perhaps the most important point on inflation is how government monopoly power over foreign currency is perhaps the greatest enabler of monetary inflation in Ethiopia. The fact that Ethiopian citizens have been barred from owning foreign currency through currency confiscation laws means they don’t have the power to hedge against debasement of the Birr by diversifying to other currencies. With Ethiopians barred from being able to own any other currency beside the birr, the value of their savings is subject to the whims of the money printer.

Freedom of choice in the currency market for everyday Ethiopians, would have served as a check against runaway government debt financed through monetary expansion. The prospect of runaway monetary inflation leading many Ethiopians to abandon the birr for other currencies and the further prospect of a Birr crisis, would have worked as a preemptive check against policies of currency debasement. It would be a force for government fiscal restraint.

But the sad reality is that Ethiopians are a captive audience to the Birr. Having virtually no access to other currency choices they sit helpless as government money printing eats away the value of their currency and their hard-earned savings along with it.

Using abstract fears of rising prices under currency liberalization in defense of a system of single-currency entrapment where the public is most exposed to monetary inflation is a little like saying it’s better to stay in a burning house rather than go outside and risk the elements.

Imports ate my foreign currency

The idea that demand can run away on its own and cause a shortage to occur is a common fallacy that crops up in attempts to explain shortages of price controlled goods. And it is no different in the Ethiopian forex market where it is the prevailing consensus as to the cause of the foreign currency shortage. The problem is Ethiopia’s insatiable desire for imports. Our import demand is so great that it goes beyond our capacity to fund it. And that’s why we have a shortage of currency. So the story goes.

The problem with this view is that it’s wholly ignorant of the role of prices in regulating supply and demand.

What happens under a market system when there is “too much demand” for something? Its price goes up. Price increases are an indication that there is not enough supply to fulfill demand at the current price. This price increase ensures that

- Whatever is in demand doesn’t run out and is conserved

- What’s in demand gets put to use wherever it’s most valued.

- A signal is sent out marking a market opportunity to increase the supply.

So you could say such chronic shortages don’t happen under a market system where prices are allowed to express changing circumstances in supply and demand.

Unfortunately the dominant narrative today has this phenomenon exactly backwards. Too much demand is not seen as an effect of price control, but believed to be the predominant cause of the shortage. Demand can somehow gallop on its own, out of the blue, become “too much” and cause a shortage.

If nothing else, what this shows is the fundamental flaw in people’s understanding of the true meaning of demand. Demand in the sense of how much people want something is practically infinite. Every person would like multiple cars, many houses, huge tracts of land just as collectively all Ethiopians want as much imported goods as they can get. But such desires are not relevant to economic decision making. If such demand was the deciding factor for shortages, we’d be queuing up for everything we buy because our desires are limitless.

The only demand that’s impactful is how much people want something at a specific price. Any account of demand that is not grounded in price is wholly irrelevant to economic thinking. This is to say that there is no such thing as fixed demand. What’s demanded always depends on the existing price.

With this grounding one can say that the prevailing explanation of import demand being responsible for the currency shortage is absurd on its face. It is not that we don’t have enough foreign currency to pay for our demands. It is that we don’t have enough foreign currency to pay for the demand at the absurdly low price at which the government has arbitrarily fixed the price of foreign currency.

Unfortunately it’s the misunderstanding that drives policy in Ethiopia. As such the country’s overarching policy agenda today is import substitution, where the government tries to replace imported goods with domestic ones. Entire ministries from the Ministry of Industry (opens in a new tab) to the Ministry of Mines (opens in a new tab) exist to serve this purpose.

But substitution is a very roundabout way of rationing foreign currency between competing import industries which dangerously empowers the government to pick and choose which domestic industries are favored. It’s a backdoor introduction of economic central planning on the domestic economy. Meanwhile foreign currency allocation is still done blindly and all incentives to increase foreign currency reserves through market incentives are still out of the picture.

The solution to the foreign currency shortage is simple when you understand the cause. An understanding of price ceilings as the underlying cause leads to the natural conclusion that removing the ceiling and allowing the true price to regulate supply and demand would solve the shortage. Sadly the chosen solution in Ethiopia is to sink down the path of central planning and controlling domestic production to fix the errors caused by the policy of forex price control. Evading simple economic truths becomes very complex, very costly, very fast.

Export your way out of the shortage

The fallacy that blames imports for the forex shortage naturally gives birth to a concomitant fallacy by way of solution, which is, export your way out of the shortage. If we could just somehow boost exports enough to the point where we had plentiful forex reserves, the shortage will be cured.

The only problem is that the biggest impediment to strengthening the export market happens to be the policy of foreign currency price fixing. The current “official” exchange rate amounts to taxing exporters close to 100% of their incoming revenue. How many companies can hope to thrive under such a tax policy? The only surprise is that there are any exporters left in Ethiopia.

The information sent out by the artificial price is one where there isn’t as great a demand for foreign currency supply. Incentives to increase supply of dollars is not the same when its price sits at 55birr per unit as opposed to the real price which is over a 100birr per unit. The volume of currency exchanged at those two prices either via remittance or through export markets is worlds apart.

And there are further implications to the domestic economy. The number of industries for whom it's profitable to operate in the export market is just not the same when foreign currency exports are taxed at 100% as opposed to not. Such level of taxation severely restricts the economic power of exporters in terms of how much resources they can command from the domestic economy for production. And it’s not just existing exporters whose volume of exports and ability to scale is stifled, but many businesses who simply don’t exist because they are not viable to turn a profit at a 100% tax rate.

Saying we want more exports, as the Ethiopian government says all the time is all well and good, but if your policy is such that you tax exporters at confiscatory rates, your words don’t align with your actions.

The government’s solution to this problem is to subsidize the export industry through tax breaks and other benefits. But what this is, is nothing more than the attempt to offset the harm done through one policy with benefits conferred by another. The government cannot know which export industry will be successful in Ethiopia out of the millions that can be started and out of which only a few will be successful. The choice as to who to subsidize is driven by the fatal conceit of central planning and is subject to political and corrupt incentives whose end result is more costly to the economy.

None of this would be necessary if the value of forex was allowed to reflect true levels of supply and demand. Indeed there is nothing better that the government can do to boost exports than liberalizing the foreign currency market.

Forex Policy and Individual Freedom

In most places around the world if you give your friend 1 dollar and get back 5 euros, or 10 euros or whatever number you agreed to, it's your business and no one else's. If you want to go into business doing that, you may have to pay a transaction tax but no one would think of getting in your way.

In Ethiopia by contrast the very act of being found with foreign currency is a crime. You often hear news reports of some guy being arrested and it’s breathlessly reported that a cache of foreign currency money was discovered in his possession (opens in a new tab) as though that’s prima facie evidence of wrongdoing. We have been so conditioned into believing a basic right is a heinous crime that no one even thinks to question why mere foreign currency possession on its own is a transgression.

With all the noise about trade imbalances, and the economic jargon of terms like float, fixed rate etc. it’s easy to lose sight of what’s really at stake, which is the basic human freedom of Ethiopians to possess and freely trade in whatever currency denomination they wish.

Why can’t you acquire and possess foreign currency to protect yourself from inflation? When the government racks up unsustainable debts in your name, then decides to pay for it by printing money and devaluing the Birr and your savings, why should you be left holding the bag? Without sovereignty over currency, you have no escape from foolish policies that destroy your currency and savings along with it.

Why are peaceful Ethiopians forced to surrender their own money? Why is it that only political elites get to determine the valuation of currencies within Ethiopia? Why is the valuation of everyday Ethiopians as expressed through market mechanisms, illegal? How is it right that you can face a 15 year jail sentence just for possessing money. How is it that advocating for the freedom of everyday Ethiopians to own currencies and exchange them at mutually acceptable prices is what’s demonized as being antagonistic to the interests of those very Ethiopians?

The foreign currency debate is really much more than shifts in government valuation this way or that. It is more than imports and exports. At bottom it’s really a question about who gets to own and control foreign currency? Who has supremacy over the country’s import market? The citizens of Ethiopia or the politicians. The real divide is not between those who’d devalue or strengthen the birr, but between those who seek a monopoly of concentrated power over foreign currency with all the economic distortions that follow and those who seek true liberalization wherein the average Ethiopian has the freedom to own foreign currency, the power to influence its price and supremacy over its use and allocation.

© Michael Tedla.RSS